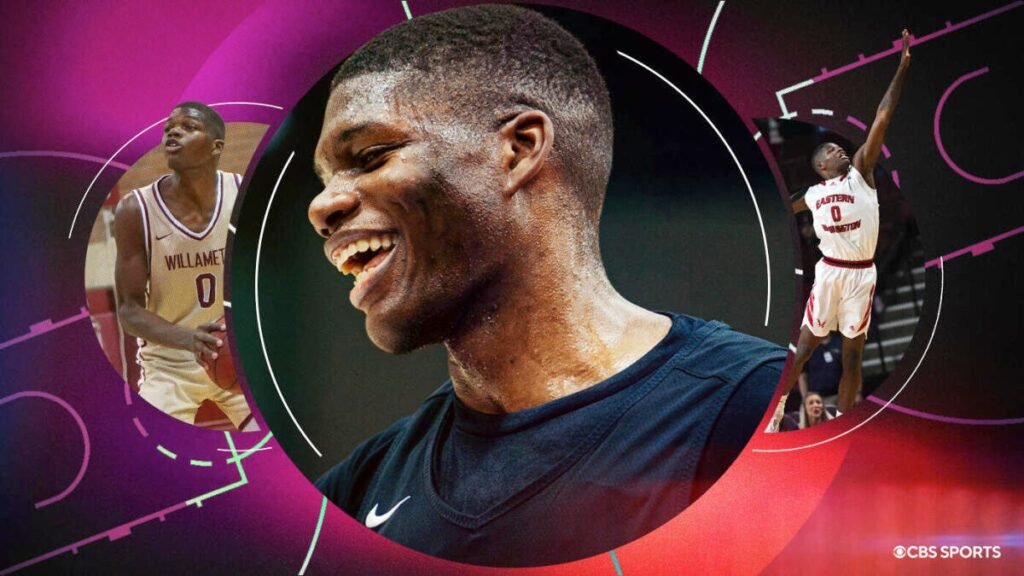

There have been 8,315 men selected into the NBA since the draft debuted in 1947.

None of them took as unlikely of a path as what Cedric Coward will achieve when his name is called Wednesday night in the first round of the 2025 NBA Draft.

Every June there are a handful of notable draft stories that stand out because of the remarkable perseverance and outstanding journeys carved en route to fulfilling a lifelong dream of being selected. Coward’s odyssey is a level beyond that. Unique doesn’t begin to describe how improbable this has all become in recent months. It is akin to throwing a thread through a needle’s eye from 50 feet away. You could try it 8,315 times and you wouldn’t lace it through.

Something infinitesimally implausible will be made official when commissioner Adam Silver walks to the podium and says these five words: “Cedric Coward, Washington State University.” Because his pathway to the NBA is more than just Washington State. It was 17 years in Fresno, California, then a year in Salem, Oregon, followed by two years in Cheney, Washington, before trekking to nearby Pullman for a year and then, for basically a blink, Durham, North Carolina.

In the 21st century, first round picks are supposed to be identified long before their 21st birthday. Coward’s story is not supposed to happen anymore. The American Basketball Industrial Complex apparatus has been honed over the decades to prevent players like him from avoiding detection.

How much of an unknown is Coward? His Wikipedia page lacks a photo and is fewer than 250 words. But should he capitalize on his potential in a way that his outrageous ascendence over the past two-plus months suggests, he can grow into one of the best rags-to-riches stories in basketball history.

The 21-year-old has managed to go from someone who didn’t make the varsity basketball team at a public high school until his junior year to vaulting to top-20 status of the 2025 NBA Draft. He has the intelligence, athleticism, body type, confidence, mechanics and leadership qualities that suggest a realistic chance at success in the best basketball league in the world. What’s more, there are three franchises holding lottery picks that are expressing genuine interest less than a week out from the draft, sources told CBS Sports.

If you’re wondering, Who is this guy and why haven’t I ever seen him? Coward hasn’t played a game in seven months.

Four years ago, he was preparing for his first season of college at Division III Willamette University in northwest Oregon. He went from there to the lower rungs of D-I, but only appeared in six games in his senior year because of a season-ending injury last November. And yet, in spite of everything historically working against him, Coward will sit in the Green Room on draft night, a lock to go in in the middle of the first round.

Nothing like this has ever happened.

“You wouldn’t think I would be here,” Coward says.

You wouldn’t. But he would. This is how Cedric Coward took the scenic route from six-win D-III player to potential top-20 NBA pick.

Raised by family, driven by Olympic legacy

Coward grew up in northeast Fresno, raised by his mom, Shanel Moore, and stepfather Ray, who Coward considers his true dad. He kept the last name of his biological father despite not having a relationship there. (Details of which Coward politely asked not to discuss). Opting to keep that biological last name was easy pickings for teasing as he grew up, but it never bothered Coward.

“The only one that truly understands the meaning of my last name is me,” Coward told CBS Sports. “It means not the definition you see in the dictionary. It means a person that has persevered through many, many challenges and revelations to get where he’s at now.”

He kept the legal surname because of the grandfather on his father’s side, Francis Coward, who remains a big influence to this day.

“I’m really close with him, super close,” Coward said. “And so to honor him, I kept the last name, because if I’m gonna do it for anybody, I’m gonna do it for him.”

Coward has close bonds with all of his grandparents. The grandfather on his mother’s side, Maxie Parks, passed down genes that contributed to Coward’s athletic 6-foot-5.25-inch frame on a tantalizing 7-foot-2.25-inch wingspan that pairs with quick-burst ability. Parks ran track at UCLA and is permanently honored in the school’s Hall of Fame because, in 1976, he was a member of the gold medal-winning 4×400 relay at the Montreal Olympics.

“His athletic hero,” Shanel said. “Maxie has medals everywhere. He wants those too. He told my father when he was very little, ‘I’m going to be just as great as you in my sport.'”

Ranking high on the reasons Coward has transformed himself into an NBA pick is his deathly serious competitive streak, something that seems straight from the mindset of his favorite player, Kobe Bryant. In fact, that ethos was passed down from Poppa Maxie, 75, who instilled a sense of athletic pride since Cedric was a young boy. Off the court, Coward is as engaging, conversational and as quick with a smile as any prospect you’ll find in this year’s class. On the court, an entirely different personality takes hold.

“If I’m going against you on the court, I’m trying to kill you. I’m trying to take your head off. That’s all it is,” he said. “When I step on the court, now it’s go time in between those four lines. It’s a battle. And you don’t win battles by being friends.”

Probably a mandatory mindset if you’re going to go from zero-star recruit to the NBA.

Shanel Moore

Coward attended Central High in Fresno and never developed into a Division I prospect while there. Standing 5-9 and weighing maybe 150 pounds at 14, he made the freshman team his first year, then JV as a sophomore before finally being good enough to play varsity as a junior — where he was captain for the next two years. Coward continues to draw motivation from the guy Kobe emulated, someone else who also didn’t make the varsity team initially: Michael Jordan.

“When people ask me, ‘What do you do for fun outside of basketball?'” Coward says, “I watch movies on basketball, documentaries on basketball. I’ve probably seen ‘The Last Dance’ six times. It’s in my Netflix downloads. I watch it on planes.”

The obsession took hold about six years ago. Before that, Coward had fluctuating investment with basketball in high school. He slipped through the scouting cracks not just because he wasn’t good enough to play varsity until 16, but also because he played small-time AAU — and not even every year. The summer before he became a junior, Coward quit the spring/summer circuit.

In retrospect, this decision makes his rise even more unlikely.

The number of active American-born NBA players who willingly opted out of AAU for at least one year during their high school days can be counted on one hand — maybe a finger. It’s just not something that happens anymore, because the system practically mandates it. Yet Coward bailed going into his junior year, a critical period for players to validate their talents and give themselves a chance to earn D-I offers.

“I didn’t play AAU because I just didn’t like the situation I was in,” he said. “I thought I was losing love for the game.”

He also wasn’t being recruited to better grassroots teams, which bothered him.

“I did not think the NBA was on the table,” his mother said. “Did I think he was going to play professionally somewhere? Yes. But I thought he was going to be in another country doing it.”

With basketball off the menu in the summer of 2019, there would be no lazing around. Coward helped Poppa Maxie build a house in coordination with Habitat for Humanity. Everything from hammering nails to shoveling sand, installing the foundation and putting in drywall. Weeks and weeks of eight- and nine-hour days in the scorching California sun. He didn’t touch a basketball for weeks.

When the house was completed, Coward felt as gratified by it as anything he’d done in his life. And another thought permeated.

“It really proved I actually loved the game so much I couldn’t be without it,” Coward said. “That was a huge turning point.”

He’d make varsity that fall, yet wasn’t sure how to make the leap as a prospect. When he returned to the AAU circuit, he’d play in smaller tournaments with minimal attendance. This was the COVID era, meaning games were restricted, college coaches weren’t attending and his opportunities were near non-existent. He admits to not being good enough.

“I probably wasn’t performing to the standard of, like, going to UC Riverside,” Coward said. “I wasn’t working as hard as I do now.”

If it was up to Coward, he would’ve attended Fresno State as a regular student and tried to walk on the basketball team, if not gone to a local college a short drive away. But his parents insisted he make good on his academic achievements and find independence. He was active in after-school clubs, doing so in part at mom’s encouragement because she knew they would be favorable on college applications (Coward was accepted to 11 universities, but only two also recruited him for basketball). He was part of the Black Student Union and the Fresno County African-American Leadership Conference Board, one of only a few high-schoolers chosen for that honor. A National High School Scholar, he also had some of the best grades in his class.

“I didn’t want to leave, but they wanted me to make sure I was comfortable being uncomfortable, and to explore the world,” Coward said.

Kendrick Arakaki / Willamette University

Willamette sits 700 miles north of Fresno in the northwest region of Oregon. Coward picked the place as much, if not more, for academics as he did basketball. The team was a terrible 1-29 in the two seasons prior to Coward arriving. Coward asked the head coach, Kip Ioane, why they weren’t any good. Ioane took all the responsibility and didn’t blame the players. The honesty endeared Ioane to Coward and made him comfortable choosing Willamette.

He couldn’t have known it then, but the decision would prove crucial for eventually being discovered less than a year later.

“I know now, in retrospect, it did him a tremendous service because he was then able not to have any other distractions but school and basketball, and now we’re here,” Shanel said.

Coward was immediately unlocked as a terrific D-III player. The Northwest Conference Freshman of the Year, he averaged 19.4 points, 12.0 rebounds and 3.0 assists on 45.3% 3-point shooting and 60.8% overall. But Willamette was still dreadful, a 6-18 outfit. Coward was perplexed.

“For me, it was never about the numbers I was getting,” he said. “I was just trying to do what I could to help us win. I remember I had a game where I had like 25, 16 and seven steals and we lost by 40 at home. It was one of the most frustrating things. It wasn’t the fact that I had a great stat line, it was the fact we lost by 40. I don’t care about my stats. I could have had two points, five rebounds and one block. I don’t care. I just want to win.”

Attendance was anemic. There’d be 150 people — if that — in the stands. What he didn’t know: There was a coach 385 miles away who’d seen him near the start of that season and was waiting to see if Coward would try his chances at Division I.

The fortuitous night that changed his future

Coward has made a lot of his own luck, but he’s also been on the serendipitous end of some fortune as well. The most crucial moment of them all might be Nov. 11, 2021. It’s the third game of his freshman year, at Portland, with the Pilots intentionally scheduling a non-Division I matchup to ease into their season. It’s noncompetitive. Portland predictably pummels Willamette, 122-78. Coward shines, though, scoring a game-high 24 points off the bench, in addition to seven rebounds and five assists.

That same night, Eastern Washington was in California preparing for its game the next day at UC Davis. EWU coach David Riley and his staff were at the team hotel. They turned on the game.

Why would they want to watch Portland play a D-III school?

Because Riley, 36, is a former D-III player at Whitworth University, which plays in the Northwest Conference — the same league as Willamette. He follows that league because of his ties to it. That’s it. If he’d never played at Whitworth, he never would’ve cared enough to turn on the game.

If he never turns on the game, he almost definitely never would have eventually recruited Coward.

If Riley never recruits Coward, it’s fair to wonder … where would Coward be right now?

But watch they did and Coward looked the part of best player on the floor. That performance would linger with Riley for months. By season’s end Coward had the numbers to justify going into the portal in the spring of 2022. EWU’s staff tracked him from afar. When Riley brought up Synergy to catch up on Coward’s tape, he didn’t watch long.

“It was a no-brainer,” Riley told CBS Sports. “It’s kind of crazy how it all kind of fell into place.”

Here’s another bit of serendipity: Former EWU assistant Arturo Ormond has Fresno roots. He previously coached at Edison High School in the city and thus did a lot of the groundwork on recruiting Coward. New Mexico State, Idaho and Southern Utah were the only other schools recruiting him, but none did with nearly the level of interest and enthusiasm.

“It was not that competitive,” Riley said of the recruitment of a future first-round NBA pick.

Coward came off the bench his first year with the Eagles as a power forward-type who played behind two established wings, Steele Venters and Angelo Allegri, both of whom had a small group of NBA teams flying to EWU to check in. Learning behind those two was a vital stage in Coward’s development. Coming from D-III, he was working for respect. There were weird transitions. He barely lifted weights at Willamette. Coward was so green, he didn’t realize he could get treatment and use EWU’s facilities whenever he wanted.

“Very naive to the process, and once he figured out what that looked like, he just kind of took it and ran with it,” Riley said. “Eventually, something clicked, where he saw Steele and ‘Gelo, how hard they were working. He knew he wasn’t meeting his level.”

And yet, his efficiency that first season was bonkers. His offensive rating was 137.9, third-best in Division I … but he logged just 21.6 minutes per game. He shot 39.4% from 3, yet took only 33 attempts from beyond the arc … averaging exactly one 3-point attempt nightly (and just 3.2 shots per game overall). He was the best off-the-bench player in the Big Sky and helped EWU to an 18-game winning streak that season.

In March, the Eagles captured a regular-season championship. A year after enduring a six-win season at Willamette, Coward was on a 23-11 team.

“The happiest moment I’ve ever had was when we won that championship at Eastern,” Coward said.

His mother agreed.

“I wasn’t there, but through the TV I could see his heart,” Shanel Moore said. “He hates to lose. In high school, they lost the championship by one shot.”

After his first season at EWU, with Venters and Allegri moving on, Coward approached Riley with a request most coaches probably wouldn’t have abided by, not in the portal era. He asked not to be recruited over.

“I know I’m good enough to fill their shoes,” Coward told Riley. “I don’t want you to bring in transfers. And they told me straight up, like, ‘OK, we believe you.'”

Coward would tell you he’s not here without the support of so many coaches over the past four years, but the one who put in the most hours and had the most belief is Pedro Garcia Rosado. In the spring, summer and fall of 2023, Coward and Rosado practically lived in the team facility. There would be three-a-day sessions with a variety of intense drills and skill work, with Coward morphing from an off-the-bench power forward to a dynamic, perimeter-capable wing.

“Whatever I asked him to do, he did it,” Garcia Rosada told CBS Sports. “He never complained about anything. He never doubted himself. He’s a person that, once he believes in you, he’s all in with you. Doesn’t matter what you tell him. He’s a person that always has a lot of questions, is very intrigued, very curious, and once you get it, he’s all-in.”

That six-month span is when Coward transformed into a future pro. The coaches reminded him of the vision often, just like he wanted. If he wasn’t the best player at EWU in his second season, he’d be “a bust.” He asked for the responsibility; it was now on him to deliver.

“I appreciate that, because I like people that really are brutally honest,” Coward said. “I don’t want you to sugarcoat anything.”

Then, early in his junior year, it was a disappointment verging on a disaster. In the opener against Utah, he was terrible.

“Everyone on the team was like, ‘Oh, shit,'” Riley said. “Like, is he ready to be on the perimeter? Are we? Is this not going to work?”

For a few weeks after that, he was still not making the jump as expected. There was anxiety but never pull-the-cord panic. By the time league play began, Coward pieced together the work from the previous eight months and became a top-three player in the Big Sky.

“That’s part of the beauty of being Eastern Washington,” Riley said. “You don’t completely lose your confidence when you’re 0-7 and having shitty numbers, because you’re playing good teams.”

Ace Bailey is taking a calculated — and dangerous — risk with his NBA future

Kyle Boone

EWU won a second straight regular-season league title, though again fell short in qualifying for the NCAA Tournament, preventing Coward from having a moment on the big stage. Coward declared for the draft, only to be denied an invite to the NBA Combine … and the G League combine. It was a harsh message.

He’s kept that on his shoulder for almost 15 months.

“I love being able to prove people wrong. I like when people tell me I can’t do it,” Coward said. “I’m gonna show you. All right, cool. I’m just going to be here, working in silence.”

Riley got the Washington State job in April of 2024, and here’s a key development that might have altered Coward’s unprecedented pathway to draft night. He put his name into the portal with the intention of following Riley to Wazzu … and then a dozen-plus high-major schools found him, with plenty of them offering big money, including Texas Tech in the high six-figures, according to multiple sources.

“He knew there was a lot of money out there, and he was gonna come back for damn near nothing at Eastern just to stick with the vision,” Riley said.

This after receiving $0 for transferring from Willamette.

Coward signed with an agent, maximized his spring workouts for NBA teams and publicly announced in late May of 2024 he’d follow Riley to Washington State. It was going to be the year he truly vaulted himself to an NBA pick. And he did.

But the way it’s happened is almost impossible.

After six games last season, when he was averaging nearly 18 points and better than seven rebounds, Coward suffered the first serious injury of his career.

IMAGN

The injury that somehow could not halt Coward’s rise

On Nov. 22, 2024, Coward’s arm was pulled while going up for a rebound in practice, while going up for a rebound. He felt a pop. “It feels wrong,” but thought, but pressed on — his team even winning its scrimmage drill moments after the tweak.

“I went home, and I was like, OK, it’s gonna be fine,” Coward said. “Worst-case scenario, I’ll tape it and play with a tape on. I’ll be all right.”

The next morning, he woke up and his arm was dead weight. Immense pain. His season was over. He knew it when he walked into the office and saw Riley, Garcia Rosado and team trainer Hailey Haukeli waiting for him. Coward would need surgery; imaging showed a shredded rotator cuff and partially torn labrum in his left (non-shooting) shoulder.

“He was very stone faced,” Riley remembered. “Then it flipped within two minutes of, ‘How I can make the most of it and find the silver lining.’ And it’s ‘the plan’s not going to change.'”

This was supposed to be the apex of his college career and the turning point to make the NBA from a small outpost in the Pacific Northwest.

“I walked out trying to be like the tough man, like I can take it,” Coward said. “Then I walked out by myself. There’s a long hallway from coach’s office to where we have to go downstairs one level to go to our locker room. And I probably cried as soon as I exited the office, where nobody could see me, I cried down the entire hallway. It was one of those you-can’t-breathe cries.”

He didn’t even tell his family he’d gotten hurt when it initially happened. He called his agent, his long-term concern being the fate of his NBA stock. He was soon back home, recovering from surgery on winter break for a few weeks, watching his teammates in every game, not even allowing the channel to be changed during commercials. When he returned to Washington State, Coward became an unofficial coach. He lived in the facility more than before, sitting in on practice plans, offering up opinions, sponging up everything.

“It’s a literal blessing in knowing that, although it was a super devastating thing that happened, it allowed me to elevate my game and my mind and body in so many ways,” Coward said. “It allowed me to understand the process, like, not everything’s gonna go how you want it to. Not even if you’re doing great things, you’re not always gonna get the result you want, and staying the course really is the biggest thing.”

Coward’s recovery was dogged and quickly ahead of schedule. He did anything to stay physically and conditioned, cautiously pushing the envelope. The staff put together a reel of his progression in the middle of the season and sent it to his agent, who forwarded the video to seven NBA teams. Many liked what they saw. Coward double-dutied with rehab and being a player-coach. He reported to Garcia Rosado on defensive scouts, even stopping a team walkthrough at one point to quiz everyone about the actions they were running.

“It was still his team, he still wanted to win,” Garcia Rosado said. “A lot of players don’t want to do all that stuff. A bunch of NBA scouts and GMs realized that. They see Cedric on the bench celebrating, supporting. The reality is, everyone can see his body and measurements, that’s obvious, but it’s the other things that are impressive. Someone who works that much, that hard, for so many days. He’s a great role model. Some players are good leaders by the way they talk to the team, but Cedric was our leader because of the way he works. No one worked with more quality.”

Life Sports Agency

Washington State finished 19-15, and at the end of the season, Coward was healthy enough to again declare for the draft and enter the portal, just in case.

Again, dozens of high-majors chased. This time, he planned to go big — Riley knew it was inevitable, considering Coward’s outstanding reputation — and so in mid-May, Coward announced he would play at Duke if he didn’t stay in the draft. He chose the Blue Devils over Alabama. Washington (which had a huge NIL offer), Florida and Kansas were also heavily chasing.

Duke was essentially an insurance policy, in the event Coward’s pre-draft process didn’t yield the results he was hoping for. By early May, he was getting good feedback but nobody really knew.

Then he went to the combine and everything changed practically overnight.

Coward tested well, aced every interview and turned into the biggest riser in the draft. His trajectory, measurables and intangibles are eerily similar to Jalen Williams’ ascension to the No. 12 pick three years ago, which is only helping Coward’s cause, considering what Williams has done in Oklahoma City.

“When I tell you champing at the bit,” says Coward, “there’s probably not even a word or not even a phrase. I was trying to eat the whole damn steak.”

At the combine, he participated in everything except the 5-on-5 scrimmages. Coward was at or near the top in hand-size for his position (9.25-inch length), was third in 3-point shooting, fourth in spot-up shooting, fourth in sprint, fifth in free throws and sixth in off-dribble shooting.

“It has been eating at me,” Coward said. “More fuel to the fire. That’s it. And this year, even though I did get invited to the combine, and all the feedback I got from this past year, or was that I performed well, it still leaves a chip on my shoulder. Like, y’all should have saw this last year.”

How Duke’s Khaman Maluach went from playing soccer in South Sudan to a 2025 NBA Draft Lottery prospect

Kyle Boone

Currently, Coward says his injured shoulder is 90% recovered. He was recently cleared for contact, but not full-blown competition. The seven-month gap he’s endured not playing basketball since last November is much longer than when he went on competitive hiatus from the sport the summer of his junior year of high school.

“It’s not wild, because I’ve seen all the work, but at the same time, it is completely crazy,” Riley said. “His ability to see himself in reality, kind of that makes sense, like to see himself. He doesn’t think he’s better than he is. Doesn’t think things are worse than they are.”

Said one source: “There’s an ‘it’ factor that you can’t quantify or put into words. It’s a rare combination that I think very few players in this league have had, and the ones that have had it, are the great ones.”

“The guy went from a post player as a D-III kid to this,” another NBA source told CBS Sports. “It might be Jimmy Butler-ish. He’s got big-time upside potential, and the worst case is he’s a solid rotation player.”

To be fair, skeptics are of course out there. Some teams may well give him a second-round grade because there’s not enough tape against high-level competition. Other teams with inexperienced GMs or risk-averse ownership will be too scared to take a chance.

“People still give me a rap now, like, ‘You haven’t played against top 100 competition,'” Coward said. “One, I wouldn’t be here if I couldn’t. And two, whatever the hell you’re saying, I don’t care, because at the end of the day, I’ll just go prove people wrong. And did people say the same thing about Dame Lillard? Did people say the same thing about Kawhi Leonard? Just think of all these other mid-major players, like Jalen Williams.”

Even with understandable hesitation, the entire package is too good for someone not to eventually say yes. Having worked out with nearly half the league in the past month, he will take his workouts up until the final days to make any outcome in his favor possible.

“For me, it’s understanding the moment I’m in now. It’s still a day-by-day process. I don’t care whether I’m projected top 20, top 10. I don’t really care. It’s: use every day to get better,” Coward says. “I want to be able to thrive because making the NBA is already hard enough, but staying in the NBA — especially because you’ve got a new sum of people always coming in — is even harder. And that’s my goal, is then to ultimately become the best I can be, and I believe I can be a Hall-of-Famer.”

It’s a lofty, perhaps irrational vision, but after reading his story, could you fault him for believing anything in his life can be achieved through basketball? He is tangible proof of concept. No one in the history of the draft has gone from D-III to low-major to mid-major, playing fewer than 10 games their final season of college, and been a first-round pick. Or even picked at all. But Cedric Coward will do it. He has manifested this. He has broken the code. His process and pathway to this point is unrepeatable, which makes his story that much more incredible.